Margaret King

Margaret King | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1773 |

| Died | 1835 (aged 61–62) |

| Occupation(s) | Intellectual hostess, writer |

Margaret King (1773–1835), also known as Margaret King Moore, Lady Mount Cashell and Mrs Mason, was an Anglo-Irish hostess, and a writer of female-emancipatory fiction and health advice. Despite her wealthy aristocratic background, she had republican sympathies and advanced views on education and women's rights, shaped in part by having been a favoured pupil of Mary Wollstonecraft. Settling in Italy in later life, she reciprocated her governess's care by offering maternal aid and advice to Wollstonecraft's daughter Mary Shelley (author of Frankenstein) and her travelling companions, husband Percy Bysshe Shelley and stepsister Claire Clairmont. In Pisa, she continued the study of medicine which she had begun in Germany and published her widely read Advice to Young Mothers, as well as a novel, The Sisters of Nansfield: A Tale for Young Women.

Childhood

[edit]

Margaret King was born into the Anglo-Irish Kingsborough family, leading members of the Protestant Ascendancy, the Anglican landed elite in Ireland who cooperated with the British Crown in governing the Kingdom. Her mother, Caroline Fitzgerald (one of the wealthiest heiresses in Ireland and first cousin of the revolutionary Lord Edward FitzGerald), was married off at 15 to Robert King, Viscount Kingsborough, later Earl of Kingston. The family seat was Mitchelstown Castle, in the north County Cork town of Mitchelstown. Margaret was the middle child among a family of nine siblings.

Tutored by Mary Wollstonecraft

[edit]Her parents, she later wrote, were "too much occupied by frivolous amusements to pay much attention to their children", so already before her third birthday, she was entrusted to governesses and tutors.[1] These included the pioneer educator and proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, to whom Margaret was a "most devoted protegee".[2]

Wollstonecraft’s tenure did not last more than a year, as, finding her haughty and affected, she could not get along with Lady Kingsborough.[3] Margaret nonetheless claimed that Wollstonecraft’s influence was profound, that she "had freed her mind from all superstitions".[4]

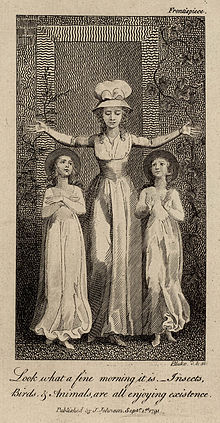

Some of the experiences of Margaret and of elder sister Mary during this year (1787–88) would make their way into Wollstonecraft's only children's book, Original Stories from Real Life (1788).[5] "Mary" is the eldest of two aristocratic young charges that a genteel and unpaid governess puts through a programme of experiential education on the model of Rousseau's Èmile.[4] The motherly governess in the framing story is called Mrs Mason, a name Margaret King adopted in later life. Wollstonecraft's experience in the Kingsborough household also appear to inform her first novel, Mary: A Fiction (1788), begun during her time in Mitchelstown: "Mary" is the unhappy daughter of haughty aristocratic parents.[4]

Outraged opinion associated Wollstonecraft's influence with the scandal that subsequently engulfed Margaret's sister. Mary, aged seventeen, eloped with her married cousin Colonel Henry Gerald FitzGerald. On the eve of the 1798 Rebellion, Margaret's brother Robert and her father were charged and acquitted of Fitzgerald's murder.[6]

For her part, Margaret traced ro Wollstonecraft "the development of whatever virtues I possess".[7] She had taught her to think for herself and to question respect and obedience commanded only on the basis of rank.[4]

First marriage, children

[edit]Margaret acquired the title Lady Mount Cashell by marrying Stephen Moore, 2nd Earl Mount Cashell on 12 September 1791. She was 19 and he 21. In 1794 her eldest brother, later George King, 3rd Earl of Kingston, married her husband's sister Helena.

The Mountcashells had seven children. The eldest son, Stephen Moore, 3rd Earl Mount Cashell, went on to graduate from Trinity College, Cambridge,[8] marry a Swiss woman, and live in several countries. He founded a farming community on Amherst Island in Upper Canada (now Ontario), and was judged "an improving and evangelical landlord".[9] The second son, Robert, was born in 1793. The third son, Edward Moore, became a Canon of Windsor Cathedral. The eldest daughter, Helena, was born in March 1795.[10] One of the younger daughters, Jane Elizabeth, married in 1819 William Yates Peel, from the political and merchant family.[11]

In 1798, her brother Robert King, 1st Viscount Lorton was involved in a scandal. He was tried for the murder of a relative who had seduced their younger sister.[12]

Radical politics

[edit]Marriage and motherhood did not temper her political radicalism. She attended the treason trials of John Horne Tooke, John Thewall, and Thomas Hardy in London in 1794, and in Dublin joined another of Lady Moira's bluestocking circle, the poet and satirist Henrietta Battier, in heeding the appeal in The Press for women to "act for the amelioration of your country in the mighty crisis that awaits her": she took the United Irish test.[13] Her mother's cousin, the United Irish leader Lord Edward Fitzgerald, and his wife Stéphanie Caroline Anne Syms were close friends. When, on the eve of the 1798 rebellion, Fitzgerald received a wound in the course of his arrest (which was to prove fatal), she intervened to prevent the news from reaching his pregnant wife, in the hope that his condition might improve and diminish the shock.[14]

The Bishop of Ossory would have had King and others of her female acquaintance in mind when, in a sermon before Earl Camden, the Lord Lieutenant, he decried the progress of revolutionary principles and atheistic philosophy through the "higher ranks" of society. The conversion of elite women to the radical cause was, he declared, "a leading object with the conspirators", who knew "the influence which female manners ever must have on society in any degree polished".[15] Margaret's eldest brother, George King, was a prominent Loyalist.

Yet despite her sympathy for the United Irishmen, there is no evidence that Margaret embraced the social egalitarianism of some of the more committed republicans. She remained "ambiguous about social distinctions". They were to remain a feature of the utopia in her unpublished novel Selene in which a young man is indeed ruined by the "ridicule of high birth and ancestry" into which he is drawn by "professed democrats".[16]

After the defeat of the insurrection in 1798, Margaret wrote pamphlets opposing the government's policy of abolishing the Irish Parliament and effecting a legislative union with the Kingdom of Great Britain.[17] Among her extensive circle at this time she counted Lord Cloncurry Valentine Lawless, Charles Fox, Helen Maria Williams, Matilda Tone, and Robert Emmet (fated to hang for attempting to renew the United Irish insurrection in 1803).[18]

The Grand Tour, and separation from Mount Cashell

[edit]In December 1801 the Cashells embarked on a grand tour as a group of "nine Irish adventurers", including the diarist Catherine Wilmot. Wilmot wrote extensive letters home, some of which were published in 1920 as An Irish peer on the continent (1801–1803) being a narrative of the tour of Stephen, 2nd earl Mount Cashell, through France, Italy, etc.[19] These describe much detail of the Cashells' life and habits, including their lavish entertaining, especially during the first nine months in Paris. In the French capital, they met Napoleon, the radical English parliamentarian Charles James Fox and, "up half a dozen flights of stairs, in a remote part of the town", Thomas Paine.[20]

In June 1802 the Cashells had another son, Richard Francis Stanislaus Moore, and Wilmot records that its godparents were William Parnel, "the Polish Countess Myscelska", and the American minister (presumably Robert Livingston, who was in post 1801–1804).

The resumption of war in Europe in March 1803 found the party in Florence. In 1804 they decamped to what they assumed was the relative safety of Rome. In Rome they were in the company of the Swiss painter, and founding member of the Royal Academy in London, Angelica Kaufmann; the epicure Lord Bristol, Bishop of Derry (who, in the Volunteer crisis of 1783 is said to have imagined himself King of Ireland);[21] the Cardinal Duke of York, brother to the Young Pretender, Charles Edward Stuart; and the Pope, Pius VII, who in his gardens "very gallantly pull’d a hyacinth and gave it to Lady Mount Cashell".[20]

While in Rome, Margaret was introduced to George William Tighe (1776–1837) of Rosanna, Ashford, County Wicklow, an Anglo-Irish gentleman with an interest in agriculture and, in contrast to her husband, with social and political views similar to her own. The two were instantly attracted and soon embarked on an affair, which in 1805 led to her husband leaving her in Germany and returning to Ireland with their children. Women in her position, wishing to leave an unhappy marriage, had few rights, decades prior to legal reform in the passage of the Custody of Infants Act 1839, Matrimonial Causes Act 1857, and Married Women's Property Act 1884. She and her husband were legally separated in November 1812. Margaret received £800 a year and a settlement of her accumulated debts, but she never saw her children again.[22]

Advice to Young Mothers and fiction

[edit]In 1813, as Margaret King Moore, she contributed to Stories of Old Daniel, Or, Tales of Wonder and Delight, Containing Narratives of Foreign Countries and Manners, and Designed as an Introduction to the Study of Voyages, Travels, and History in General. This was a collection by The Juvenile Library, the London team of William Godwin, widower of her governess-mentor Mary Wollstonecraft, and his second wife, Mary Jane Clairmont.[23] She had visited and grown friendly with them when she was in London in 1807.[24] The book's popularity resulted in her adding new stories to subsequent editions, the last (and fourteenth) of which appeared in 1868.[18]

Free with Tighe to follow her own course, in Germany she studied medicine at University of Jena, attending lectures disguised as a man, because medical education was forbidden to women. She was as tall as a man, and cultivated a surly and taciturn persona, to keep away curious acquaintanceships. She continued her studies in Italy, with professor of surgery, Andrea Vaccá Berlinghieri of the University of Pisa. She is known to have conducted a dispensary for the poor in Pisa, akin to the Bloomsbury Dispensary for the Relief of the Sick Poor in London.

In 1823 she published a very popular practical medical guide, Advice to young mothers on the physical education of children, by a grandmother, which went through numerous editions in several countries including Britain and the United States. Posthumous Italian editions, translated by Margaret's personal physician, were published under the name Contessa di Mount Cashell—Irlandese.[25] Among other un-orthodoxies, in her Advice she insisted on the superiority of female midwives (the competing worldview was the rise of male obstetricians such as William Smellie), and the benefits of the mother herself breastfeeding (as opposed to "throwing" her child on "the bosom of a stranger", i.e. a wet nurse). Breastfeeding, she noted, delays the likelihood of conceiving, thus avoiding the risks of near-constant pregnancy (which she had witnessed in her mother). She also issued a stern injunction against ever "wounding a daughter's sensibility, or mortifying her pride".[25]

Following the success of the book, she undertook to translate medical works from German.[18] She maintained her interest in literature, publishing a two-volume novel The Sisters of Nansfield: A Tale for Young Women (1824).[26] It is the story of two young women who are induced by the untimely death of their father to consider society and its conventions with a more critical eye. Unpublished, and dating from 1823, is a manuscript for a three-volume novel, Selene. Despite her nonconformity, it suggests that Margaret remained "ambiguous about social distinctions". An aristocracy is a feature of the novel's lunar utopia, and one of her protagonists, a young man, is indeed ruined by the "ridicule of high birth and ancestry" into which he is drawn by "professed democrats".[16] The story reads as a critique of contemporary English society, its mores and literary standards. But through its central female character, it is also a mediation upon Margaret's own experience as a woman including the pain of an unhappy socially-dictated marriage, and of recuperation through a second relationship enjoyed in relative seclusion.[27]

Life and circle in Italy

[edit]George and Margaret moved to Tuscany, where they called themselves "Mr and Mrs Mason", taking the name of the maternal governess in Wollstonecraft's early novel.[25] Margaret developed a reputation as a "no nonsense grande dame",[28] and the couple set up home at Casa Silva, Pisa, with their daughters Lauretta and Nerina.

They were visited there in 1820 on an almost daily basis by a young threesome: the poet Percy Shelley, his wife the writer Mary Shelley (daughter of Godwin and Wollstonecraft, and already author of Frankenstein), and their translator, her stepsister Claire Clairmont. She felt maternal towards the women, as they were both in a sense daughters of her life-changing motherly governess. She offered "sage advice" to Shelley about his health and to Clairmont about her career. She introduced them all to a new intellectual and social circle in Pisa, and helped Mary set up her household, finding them pleasant lodgings and advising on servants.[29]

Margaret is the "lady, the wonder of her kind, whose form was up born by a lovely mind" whom Shelley celebrates in his poem "The Sensitive Plant",[22] and she helped kindle "a new-found sense of radicalism".[30] Tighe encouraged Shelley in his reading of Humphry Davy[31][32] and Thomas Malthus.[33] Their association ended when, in July 1822, Percy Shelley drowned in a storm in the Gulf of La Spezia and Mary Shelley returned to England with their only surviving child, Percy Florence Shelley.

Widowed in October 1822, Margaret married Tighe in March 1826. In 1827, only a year after their formal union, Margaret and George Tighe separated. That same year, she began hosting a fortnightly salon in her house in Pisa, the Accademia dei Lunatici (Society of Lunatics)[18][34] Those in attendance included the writers Giacomo Leopardi and Giuseppe Giusti, who would play an important role in the Italian patriotic revival.[35]

Claire Clairmont lived with Margaret, now again calling herself Lady Mount Cashell,[34] in the 1830s, looking on her as a mother, and considering that time the happiest in her life.[35] Clairmont was to maintain her ties and correspondence with Margaret's second family into the 1870s:[24] with her daughters Anna Laura Georgina "Laurette" Tighe (1809-1880) who was to write fiction under the name Sara Tardy,[36] and Catherine Elizabeth Raniera "Nerina" Tighe (1815-1874) who married the Italian parliamentarian Bartolomeo Cini It.[37]

Margaret, Lady Mount Cashell, died in January 1835 and was buried in the Old English Cemetery, Livorno (then known to the English as Leghorn). Tighe survived her by two years. She was described, in the 1920 introduction to Wilmot's diaries, as "socially charming and attractive, highly cultivated, upright and refined", but "harsh to her children, a Freethinker in religion, and imbued with what were then the most extravagant political notions".[19]

Works

[edit]- with Charles Lamb, William Godwin, Henry Corbould, and S. Springsguth, Stories of Old Daniel: Or, tales of wonder and delight (1813)

- Continuation of the Stories of Old Daniel (1820)

- Advice to Young Mothers on the Physical Education of Children, by a Grandmother (1823)

- Selene (unpublished three-volume novel) (1823)

- The Sisters of Nansfield: A Tale for Young Women (two-volume novel) (1824)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Allen-Smith, Natascha (24 October 2018). "Cross-Dressing, Elopement and Travels with Percy Shelley: the extraordinary life of Margaret King". Leeds Museums & Galleries. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ [1]Melissa Benn's review of Lyndall Gordon's biography of Mary Wollstonecraft, Vindication

- ^ See, for example, Todd (MW), 106–7; Tomalin, 66; 79–80; Sunstein, 127-28.

- ^ a b c d Todd, Janet (2003). "Ascendancy: Lady Mount Cashell, Lady Moira, Mary Wollstonecraft and the Union Pamphlets". Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr. 18: (98–117) 99, 101, 116. doi:10.3828/eci.2003.9. ISSN 0790-7915. JSTOR 30070996. S2CID 165205783.

- ^ Tomalin, 64–88; Wardle, 60ff; Sunstein, 160-61.

- ^ Todd, Janet (2004). Rebel Daughters, Ireland in Conflict 1798. London: Penguin. pp. 224–234, 241–249. ISBN 0141004894.

- ^ Margaret to William Godwin, 8 September 1800, in Kenneth Neil Camerson ed. (1961), Shelley and his Circle, 1773-1822 (2 volumes), 1, Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, p. 84.

- ^ "Kilworth (Stephen), Lord (KLWT810L)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Wilson, Catherine Anne (1994). New Lease on Life: Landlords, Tenants, and Immigrants in Ireland and Canada. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780773564282.

- ^ Todd (2004), p. 145

- ^ George Peel, 'Peel, William Yates (1789–1858)’, rev. M. C. Curthoys, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 18 May 2017

- ^ Todd, Janet (2004). Rebel Daughters, Ireland in Conflict 1798. London: Penguin. pp. 224–234, 241–249. ISBN 0141004894.

- ^ Todd (2003), p. 185

- ^ "Moore, Margaret Jane ('Mrs Mason') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". dib.ie. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ A Sermon Preached before his Excellency John Jeffries, Earl Camden, Lord Lieutenant, President and the Members of the Association for Discountenancing Vice in St. Peter's Church 22 May 1798, by the Right Revd Thomas Lewis O'Beirne D. D., Lord Bishop of Ossory (Dublin, 1798), p. 10

- ^ a b Janet Todd (2003), p. 103

- ^ [Ascendancy: Lady Mount Cashell, Lady Moira, Mary Wollstonecraft and the Union Pamphlets Janet Todd Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr Vol. 18, (2003), pp. 98–117 (article consists of 20 pages) Published by: Eighteenth-Century Ireland Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30070996]

- ^ a b c d Clarke, Francis (2009). "Moore, Margaret Jane ('Mrs Mason') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". dib.ie. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ a b Wilmot, Catherine (1920). An Irish peer on the continent (1801-1803) being a narrative of the tour of Stephen, 2nd earl Mount Cashell, through France, Italy, etc. London: Williams and Norgate.

- ^ a b Smith, Janet Adam (25 June 1992). "Irish Adventurers". London Review of Books. Vol. 14, no. 12. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ Chamberlain, George Ashton (1913). "Frederic Hervey: The Earl-Bishop of Derry". The Irish Church Quarterly. 6 (24): (271–286), 273. doi:10.2307/30067555. ISSN 2009-1664. JSTOR 30067555.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Sarah (3 December 2017). "When Mary Shelley met Lady Margaret". The independent. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "Margaret Jane King Moore: Stories of Old Daniel: or Tales of Wonder and Delight". The Literary Encyclopedia. Volume 1.2.4: Irish Writing and Culture, 400-present. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ a b Before Victoria: extraordinary women of the British romantic era p. 49 by Elizabeth Campbell Denlinger, 2005.

- ^ a b c Garman, Emma (24 May 2016). "A Liberated Woman: The Story of Margaret King". Longreads. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Moore, Margaret King; Longman, Hurst; Spottiswoode, A. and R. (1824). The sisters of Nansfield. A tale for young women. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. London : Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green.

- ^ Markey, Anne (2 October 2014). "Selene: Lady Mount Cashell's Lunar Utopia". Women's Writing. 21 (4): 559–574. doi:10.1080/09699082.2014.913863. ISSN 0969-9082. S2CID 154946346.

- ^ Mary Shelley: romance and reality by Emily W. Sunstein, p. 175.

- ^ Young Romantics: The Shelleys, Byron and Other Tangled Lives by Daisy Hay, 2010, p. 184

- ^ Shelley and the Revolution in taste: the body and the natural world by Timothy Morton, p. 232

- ^ Morton, Timothy (1999). "Shelley". In McCalman, Ian (ed.). An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: British Culture 1776–1832. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 702–703. ISBN 9780199245437.

- ^ Adamson, Carlene (1997). The Witch of Atlas Notebook: A Facsimile of Bodleian MS. Shelly Adds., E.6, Volume 5. New York and London: Garland Publishing. p. Introduction, p. xlvi.

- ^ Morton, Timothy (1994). Shelley and the Revolution in Taste: The Body and the Natural World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-521-47135-0.

- ^ a b "archives.nypl.org -- Mount Cashell-Tighe-Cini family papers". archives.nypl.org. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b Todd (2004), p. 332.

- ^ "Author: Tardy, Laura 1809-1880". Italian Women Writers. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Joffe, Sharon (1 September 2016). The Clairmont Family Letters, 1839 - 1889: Volume I Front Cover. Routledge. pp. 234–236. ISBN 9781134847655. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

References

[edit]- Clarke, Francis (2009). "Moore, Margaret Jane ('Mrs Mason')", Dictionary of Irish Biography. dib.ie.

- Garman, Emma (24 May 2016). "A Liberated Woman: The Story of Margaret King". Longreads.

- Sunstein, Emily. A Different Face: the Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1975. ISBN 0-06-014201-4.

- Todd, Janet (2000) Mary Wollstonecraft: A Revolutionary Life. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-231-12184-9.

- Todd, Janet (2003), "Ascendancy: Lady Mount Cashell, Lady Moira, Mary Wollstonecraft and the Union Pamphlets", Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr. 18: 98–117. doi:10.3828/eci.2003.9. ISSN 0790-7915. JSTOR 30070996

- Todd, Janet (2004), Rebel Daughters: Ireland in conflict 1798. London: Penguin. ISBN 0141004894

- Tomalin, Claire (1992). The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft. Rev. ed. 1974. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-016761-7.

- Wardle, Ralph M. (1951), Mary Wollstonecraft: A Critical Biography. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Wilmot, Catherine. An Irish peer on the continent (1801–1803) being a narrative of the tour of Stephen, 2nd earl Mount Cashell, through France, Italy, etc.

Further reading

[edit]- The Sensitive Plant: A Life of Lady Mount Cashell by Edward C. McAleer; University of North Carolina Press, 1958

- Advice to young mothers on the physical education of children, by a grandmother. Florence, 1835 fulltext here